Entry and Exit TrajectoryBy Susan Ellis, December 2007

|

Opportunities in life come by creation, not by chance. You yourself, either now or in the past, have created all opportunities that arise in your path. Since you have earned them, use them to your best advantage. |

In the tip on The Extra Crossover – November 2007 we discussed the exit line, also known as the exit trajectory, to follow to allow that last extra crossover. If you are trying to hug the last two blocks too tight you are not able to lean as much or as far into the straight, and therefore are forced to start your straight too early, sacrificing that last vital crossover.

By the same token, if the exit trajectory carries you too far off the 5th, 6th, and 7th blocks you are wasting space and end up finishing too early on the exit as well. It’s like skating a rectangle instead of an oval. In many cases this is caused by the trajectory on the entry. Many skaters try to ‘jam’ the entry too close to the first and second blocks. This causes a multitude of problems to start snowballing.

First, because you have ‘jammed’ the entry, you have no room to ‘lay in’ (see The Corner Lay In – December 2004). And if you can’t lay in, you aren’t leaning as much and driving your weight forward in to the corner. And if you aren’t moving your weight forward you can’t carve on the ball of the foot and your blades will continue to track in a straight line towards the end boards on the entry or out of the corner at the 5th block. While you can get away with this at slower speeds and can actually carve pretty efficiently on the heel to help you turn, you can’t get away with it at high speeds where the centrifugal force (CF) is greater. You need to create the space to allow for a good lay in to allow you to project your weight forward and in.

Your last left straightaway push should propel your whole body back out away from the first block, thus creating space for the lay in off of the right skate. The lay in carves a little bit outward while you are slightly on the outside edge, then starts to carve back in towards the blocks as your weight comes forward and in to the turn. Many skaters rush this lay in process and therefore come back in too soon and set the left down too close to the second block. This will cause the skate to be pointing toward the end boards as you have no room to do otherwise. Having patience and taking the time to extend the lay in, and staying away from the second block will allow you to set the skate down at an angle pointing more towards the 3rd block. This allows you to continue leaning and bringing your weight forward to help you carve. Now you are in better position to set your right skate down again at an angle pointing more towards the apex block and not the end boards, which will again allow you to continue bringing your weight forward.

This is the critical turning point on the track. There are only two places you can turn effectively on your blade – the heel, which works well at lower speeds, but try to ride it at max speed and you fall. The other place you can turn is the ball and you need to bring your weight forward to do this. If you don’t have the ideal body position at this point, even though you are trying to bring your weight forward, CF keeps pushing you back to mid-blade and then your blade tracks straight. On the right skate, even though your push does end up mid-blade, you still need to bring it forward to carve before the push to bring your blade pointing toward the 5th block. On the left, it is easier to keep your weight forward, keep the carve going all the way through the push and finish through the ball. Remember, keeping your chest down, belly touching thigh and butt tucked under you are key to your ideal body position.

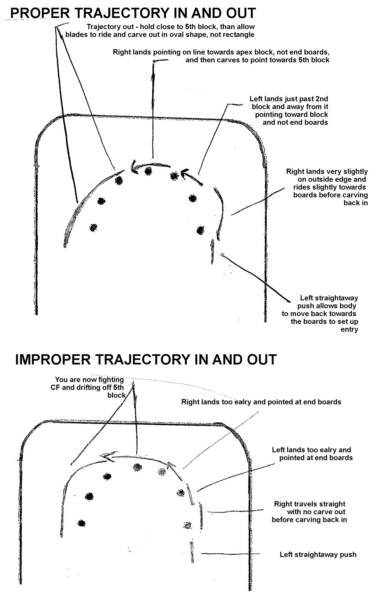

The diagram below shows the proper trajectory in and out for a narrow entry (one crossover in to the apex), and the improper entry and exit. The same principle applies for a wider entry (two crossovers in to the apex). In general, for most basic track patterns, whether you are using a narrow entry, or a wider entry, you need to be close to the 3rd, 4th, and 5th blocks, and away for the first two and last two blocks. Keep in mind there are times when you need to vary this either to block passes or to set up passes.

If you have not read Tracks – January 2005, you should read through it for more about different track patterns.

By the same token, if the exit trajectory carries you too far off the 5th, 6th, and 7th blocks you are wasting space and end up finishing too early on the exit as well. It’s like skating a rectangle instead of an oval. In many cases this is caused by the trajectory on the entry. Many skaters try to ‘jam’ the entry too close to the first and second blocks. This causes a multitude of problems to start snowballing.

First, because you have ‘jammed’ the entry, you have no room to ‘lay in’ (see The Corner Lay In – December 2004). And if you can’t lay in, you aren’t leaning as much and driving your weight forward in to the corner. And if you aren’t moving your weight forward you can’t carve on the ball of the foot and your blades will continue to track in a straight line towards the end boards on the entry or out of the corner at the 5th block. While you can get away with this at slower speeds and can actually carve pretty efficiently on the heel to help you turn, you can’t get away with it at high speeds where the centrifugal force (CF) is greater. You need to create the space to allow for a good lay in to allow you to project your weight forward and in.

Your last left straightaway push should propel your whole body back out away from the first block, thus creating space for the lay in off of the right skate. The lay in carves a little bit outward while you are slightly on the outside edge, then starts to carve back in towards the blocks as your weight comes forward and in to the turn. Many skaters rush this lay in process and therefore come back in too soon and set the left down too close to the second block. This will cause the skate to be pointing toward the end boards as you have no room to do otherwise. Having patience and taking the time to extend the lay in, and staying away from the second block will allow you to set the skate down at an angle pointing more towards the 3rd block. This allows you to continue leaning and bringing your weight forward to help you carve. Now you are in better position to set your right skate down again at an angle pointing more towards the apex block and not the end boards, which will again allow you to continue bringing your weight forward.

This is the critical turning point on the track. There are only two places you can turn effectively on your blade – the heel, which works well at lower speeds, but try to ride it at max speed and you fall. The other place you can turn is the ball and you need to bring your weight forward to do this. If you don’t have the ideal body position at this point, even though you are trying to bring your weight forward, CF keeps pushing you back to mid-blade and then your blade tracks straight. On the right skate, even though your push does end up mid-blade, you still need to bring it forward to carve before the push to bring your blade pointing toward the 5th block. On the left, it is easier to keep your weight forward, keep the carve going all the way through the push and finish through the ball. Remember, keeping your chest down, belly touching thigh and butt tucked under you are key to your ideal body position.

The diagram below shows the proper trajectory in and out for a narrow entry (one crossover in to the apex), and the improper entry and exit. The same principle applies for a wider entry (two crossovers in to the apex). In general, for most basic track patterns, whether you are using a narrow entry, or a wider entry, you need to be close to the 3rd, 4th, and 5th blocks, and away for the first two and last two blocks. Keep in mind there are times when you need to vary this either to block passes or to set up passes.

If you have not read Tracks – January 2005, you should read through it for more about different track patterns.